There are three great historic mansions in California that are full of ghosts. There’s the Winchester House, which is full of actual ghosts. Then there’s the Hearst Castle, which is full of the ghosts of history, old Hollywood, print news, and dare I say it, Rosebud. Last, but not least, there’s Scotty’s Castle, which is full of ghosts of old stories. Out of the three, Scotty’s Castle is the most remote, as it is in the far Northern corner of Death Valley National Park, miles and miles away from cities, towns, and civilization. Despite its remote location, Scotty’s Castle holds its own as one of the big three, and depending on your perspective, may even be the most interesting, beautiful, and compelling.

Ubehebe Crater

Ubehebe Crater

In my opinion, there are two types of people in the world: those that will walk down into a potentially active volcanic crater, and those that will not climb down into a potentially active volcanic crater, and instead, prefer to watch the first group from the volcanic crater’s rim. I suppose I’d be even willing to say that there’s even a third class of people, those that want to be nowhere near a potentially active volcanic crater, but they’re probably not reading this article, except as a cautionary tale of what to stay away from, so we won’t worry about them today. If you’re a member of one of the first two classes of people, and you’re in Death Valley, you’re in luck: the Ubehebe Crater is available for those who like to stand on the rim and watch, and it is available for those who like to hike. And, if you are of that third class of people that avoids volcanoes, now you know not to go to the northern portion of Death Valley National Park.

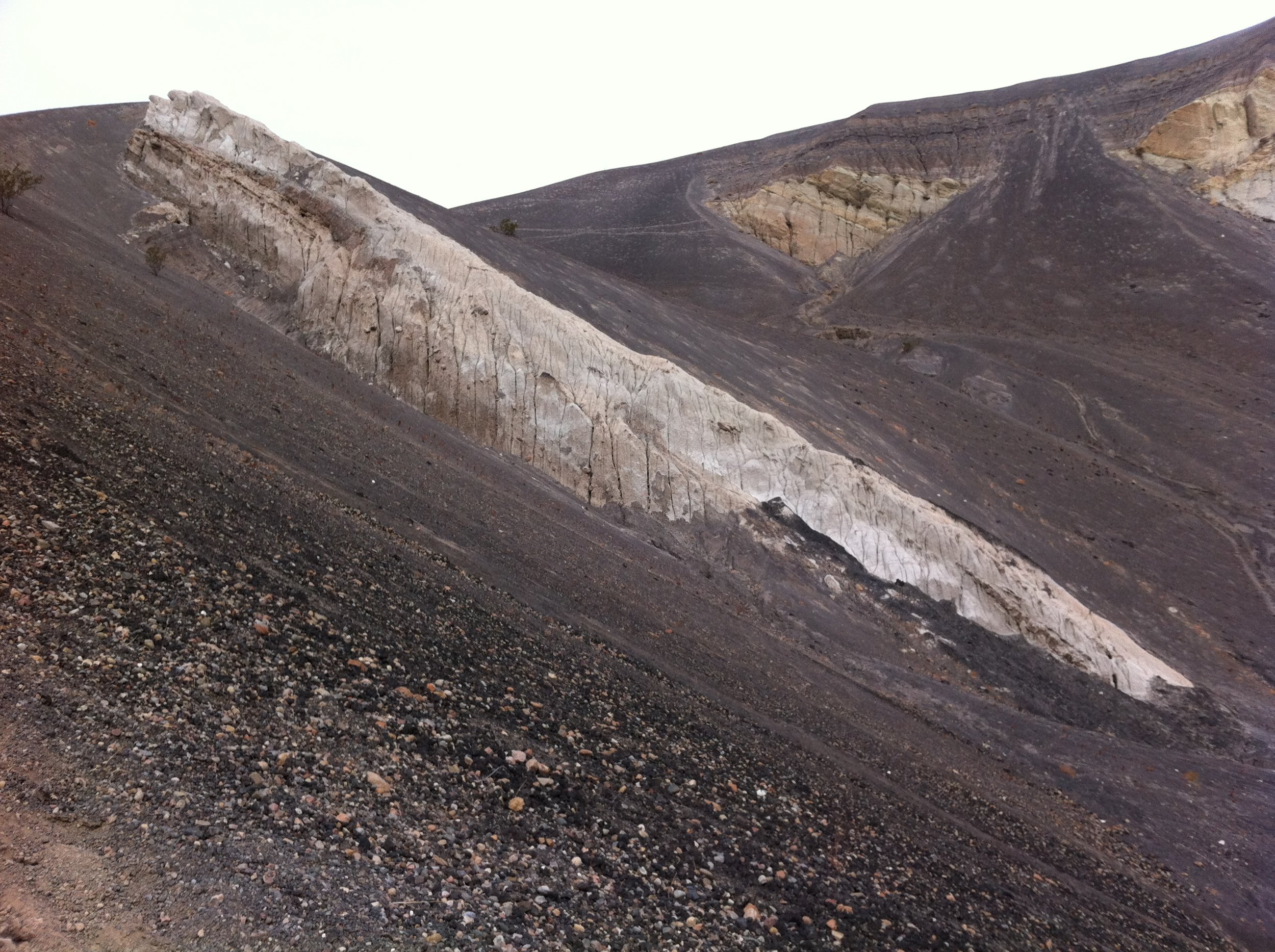

The Ubehebe Crater is one of many volcanoes in Death Valley National Park, and it is a “Maar Volcano” in that it was created by a giant steam and gas explosion that occurred when hot magma from the Earth’s core reached a pocket of ground water. When this occurred, the intense heat immediately flashed the water into steam, which then expanded until the pressure was released by a fairly large bang. If you’re into rocks, as I am, this is a sort of geologic two-for-one opportunity in that you get to go into a volcanic crater of a maar volcano – not something that happens every day! As for the amount of risk, well, while the volcano has not erupted for at least three hundred years, there is no magma underneath the area presently, so the risk is probably minimal, at best.

Directions:Ubehebe Crater is located five miles North of the Grapevine Visitor Center to Death Valley National Park, and the way to the crater is well signed. Even if there were no helpful NPS signs, you would know that you were approaching the crater when you started to pass through large expanses of black cinder fields that look like the surface of the moon. At the middle of the NPS loop road there is a parking area, and interpretive panels regarding the crater. At the interpretive panels, you will likely meet a number of people who have a number of theories about the crater – one time I was told that it was the result of a meteorite strike; another time, I was told that the NPS Panels were incorrect due to a creationist perspective, but since you have read this article, you will be prepared to impress people with your knowledge that the crater is a Maar volcano. Once you are done discussing the particulars of the crater with friends and or total strangers, you will have to decide whether you are a crater walker, or a rim-walker-watcher-of-crater-walkers.

If you’re the latter class of people, I don’t have much to say other than the standard, “enjoy the view”. If you’re a crater walker, here’s what I have to say: the way to the bottom of the crater is very easy. In fact, it is so easy; you will feel like you are sliding. This is, in fact, because you are likely sliding. You will be traveling over loose volcanic rock and scree which naturally wants to obey the force of gravity, and wants to help you obey the force of gravity by coming to rest at the lowest point, the crater floor. Even though the crater is 600-770 feet deep, you will traverse this distance quickly, and I suspect you will find yourself at the bottom within ten to fifteen minutes. Once you are at the bottom, there’s plenty of things to explore – more volcanic rocks, and the cracked dry surface of many evaporated seasonal lakes. If you’re feeling daring, you can head into the alluvial tunnels on the Eastern side as well, although from what I could find, none extend back very far, and all would appear not to be very stable.

Once you are done at the crater bottom, you will look up and marvel at how tiny the non-crater explorers still sitting on the rim looking at you appear. Similarly, they will be marveling at how tiny you look at the bottom. At that point, you will realize that you have a very steep climb back to the rim. This is the point where distance factors in: whether you believe it or not, you will have likely only gone .25 (1/4) to .50 (1/2) miles to the bottom of the crater. What that means is that you have .25-.50 miles to ascend over 500 feet of vertical terrain. To add insult to injury, while the scree helped you going down, it will now hinder you going up. At times on the ascent it will feel like you are walking through quicksand. It is precisely for this reason that I will call the hike moderate: no matter how good of shape you are in, you will work to get out of the crater. It is also worth noting that when you reach the top, you will feel an enormous sense of accomplishment; however, the non-crater walkers will not want to share it with you, as they likely thought you were crazy to attempt the hike in the first place. Although it may not seem like it, this hike is only a half-mile to mile roundtrip!

Tips: Take plenty of water. Even on a cold day, you will work up a sweat coming out of the crater. On a hot day, you may emerge completely soaking wet. Know your limits; pace yourself, and do not attempt the climb in triple digit heat at a world setting pace.

See you in the crater!

Mesquite Flat Sand Dunes

If you play your cards right, you can follow the previous posts from a snowy 11,000 foot peak (Telescope Peak), past some unique structures (the Charcoal Kilns and Eureka Mine), through an ancient canyon with cracked granite blocks (Mosaic Canyon) down to rolling sand dunes (Mesquite Flat) all within a day. That alone should make Death Valley a “must-do” in anyone’s book – I personally can’t think of another place world-wide where you can traverse such a variety of terrain in a day or less. Granted, if you’re going to do all of those things in a day, you’re going to need to get an early start, and move quick, but it is indeed possible.

Mosaic Canyon

Do you like rocks? I like rocks. I’m constantly staring at rocks; picking up rocks, and trying to analyze rocks. Part of my interest in rocks is based on the fact that I’m wondering, “Is this safe to climb? Will this hold my weight? Can I traverse it?” and part of my interest lies within a much simpler explanation: the rule of cool (“ROC”). Rocks, in my opinion, are cool. Think about it for a minute: rocks are the very bones of the planet; forged in the molten interior before being slowly exposed on the surface. Even if you disagree with my analogy above, and say that rocks are more like the soul of the planet, dark and inscrutable, or some other metaphor, rocks are cool because they are time capsules. Any geologic feature, large or small that one gazes upon probably stood for millions of years, and during that time, was probably altered by heat, wind, water, ice, or platetechtonics. If nothing else, the long view of earth’s history gives you pause – that rock there that you’re sitting on? Probably stepped upon by dinosaurs; and it’ll probably be present long after you’re gone. Then again, if you don’t want to think about such big picture things, it’s easiest to say what I said above: rocks are cool.

Eureka Mine, Harrisburg Ghost Town, Aguereberry Camp

As if there weren’t enough interesting things about Death Valley National Park, here’s one more for you: the park is honeycombed with tons of abandoned mines, representing a bygone era of mineral exploration and exploitation. Many of these mines can be seen from the trail, most notably in the Golden Canyon region, but a majority – if not all of these mines may be unsafe, due to a variety of factors – the mine may not be seismically stable, there may be hazardous gasses (methane), or there may be morlocks or other serious hazards within the mine. Fortunately, should you have the itch to explore a mine in a safe manner; there is an option for you: the Eureka Mine (provided you are headed there during the right season).

Wildrose Peak

Some people climb mountains for the challenge; some people climb mountains because they have a burning desire to be atop high places; some people climb mountains for the physical activity; and some people climb mountains just because they’re there. There’s a million reasons why people climb mountains, and if you run into people on the trail, it’s always interesting to hear why people are there, what they are doing, and if they are lost, help them out by giving them directions and encouragement. One of the most honest reasons I’ve heard for climbing a mountain was on Wildrose Peak by a transplanted Frenchman named Bernard who was living in Los Angeles. Wildrose Peak, incidentally, is the small sister of Rogers, Bennett, and Telescope in the Panamint Range of Death Valley, clocking in at 9,064 feet. On that trip, I had been on a climbing tear – I had powered up Whitney in winter conditions on Saturday, and bagged Telescope, Bennett, and Rogers on Sunday. It was now a Monday, and rather than take it easy – I decided to climb Wildrose Peak.

Telescope Peak

Telescope Peak, in my mind, is a hike full of contrasts. In 2002, I solo climbed Mt. Whitney in day at the end of May, and then got in my car and drove into Death Valley to camp at Mahogany Flat. At sunrise, I was up and on the Telescope Peak trail, and after a few hours of vigorous hiking, had summited Telescope, Bennett, and Rogers well before the day was half over. On that day, it felt like the trail positively flew away under my feet. Then again, I suppose anything after Mt. Whitney the day before would seem easy. However, on a subsequent trip to Telescope Peak, the stretch of trail from Arcane Meadows to the summit seemed to me to be the longest trail ever created. Two things are clear about the Telescope Peak trail: first, that it winds up and around to the 11,331 summit of Telescope Peak, which is the highest mountain in Death Valley National Park and the Panamint Range; and second, that it has stunning views of the surrounding terrain.